For my first “screen-printing” try last month (Nov. 2024), I was invited to reflect on place and “otherness” in those places. Admittedly I have become an avid Tenkara fisherman (a type of fly-fishing) and have become a trout-addict. The brook trout, in particular, are elusive and endearing. This simple drawing became what you see here as the screen itself stained in these colors. The work is a meditation on “seeing”: how I see (or cannot see) life in the river, and the life I see when I’m fortunate enough to land these amazing creatures in my net. I always take a moment to look the fish in the eye, primal life grounding. A simple meditation named using the Anishinaabe word for brook trout (or “trout with spots on it”).

Lock Screens & Screen Savers

I’m kicking off a new approach to this whole screensaver/lock-screen-digital-offerings thing!

Starting today, August 30, I’m selling digital images of “Calendula” and “Hibiscus” for 4 weeks, concluding on September 27. The new twist is that after that time period, I’ll be collecting and drawing from the list of names of those who purchased and the prize is the original work of art! So that means (for example, if you purchase “Calendula,” then you’ll be entered in the drawing for that one and vice versa.

Just to be clear, below are the links to each digital image:

Once you’ve purchased the image, my ask as well is that you share an image on social media of your phone or computer with that artwork and tag me @pokskape and add the hashtag #pokandsee.

Yes, you can make multiple purchases of the same image and yes, I’ll enter your name in the drawing for that number of times.

Yes, you can purchase both and you will be entered for both!

And yes, if you already purchased one of those images recently prior to this announcement, you will be entered into the drawing!

Thanks, in advance, for your support!

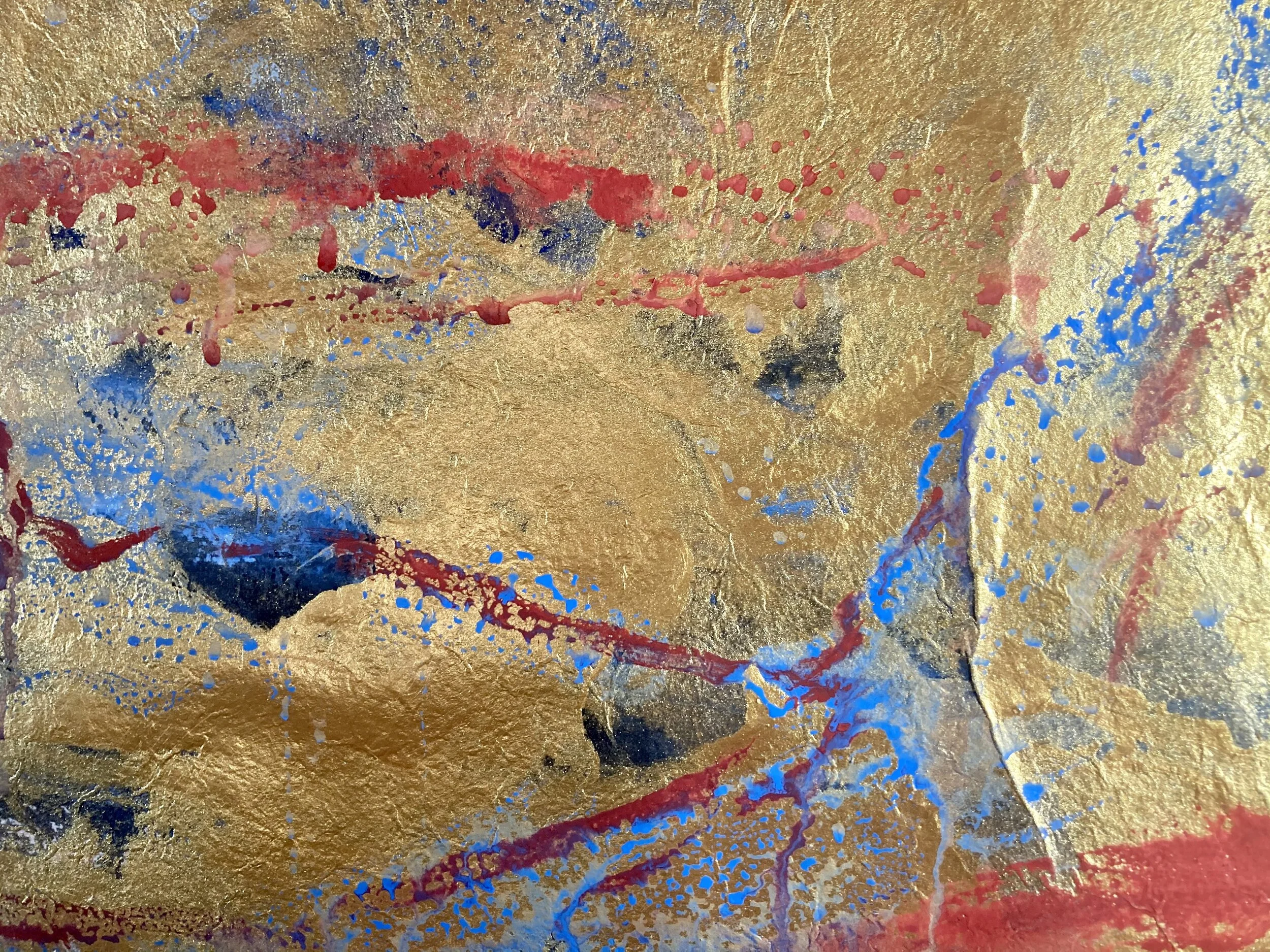

It's been too long: layers, primary colors, and Jacob Lawrence

Although this work is in progress, these two images show a progression. I’ve been focused on multiple layers of paint and color focusing the first layers on primary colors. The most recent layer on the right shows the current state as I seek to allow the first layers to still play a role without being overt. My intent is to allow the layers to be discovered without being obvious or flamboyant. The primary color effort has been inspired by a book I picked up about Jacob Lawrence who masterfully worked with similar color visions. I do take time to look at this piece prior to the subsequent layer, but I think it’s close!

The two images below, also show a slight progression. I’ve never paid any attention to acrylic paint, but have experimented with some gold acrylic paint in both works in this post. I have no interest in the toxic smells that normally come from oil based metallic paints. Again, more layers.

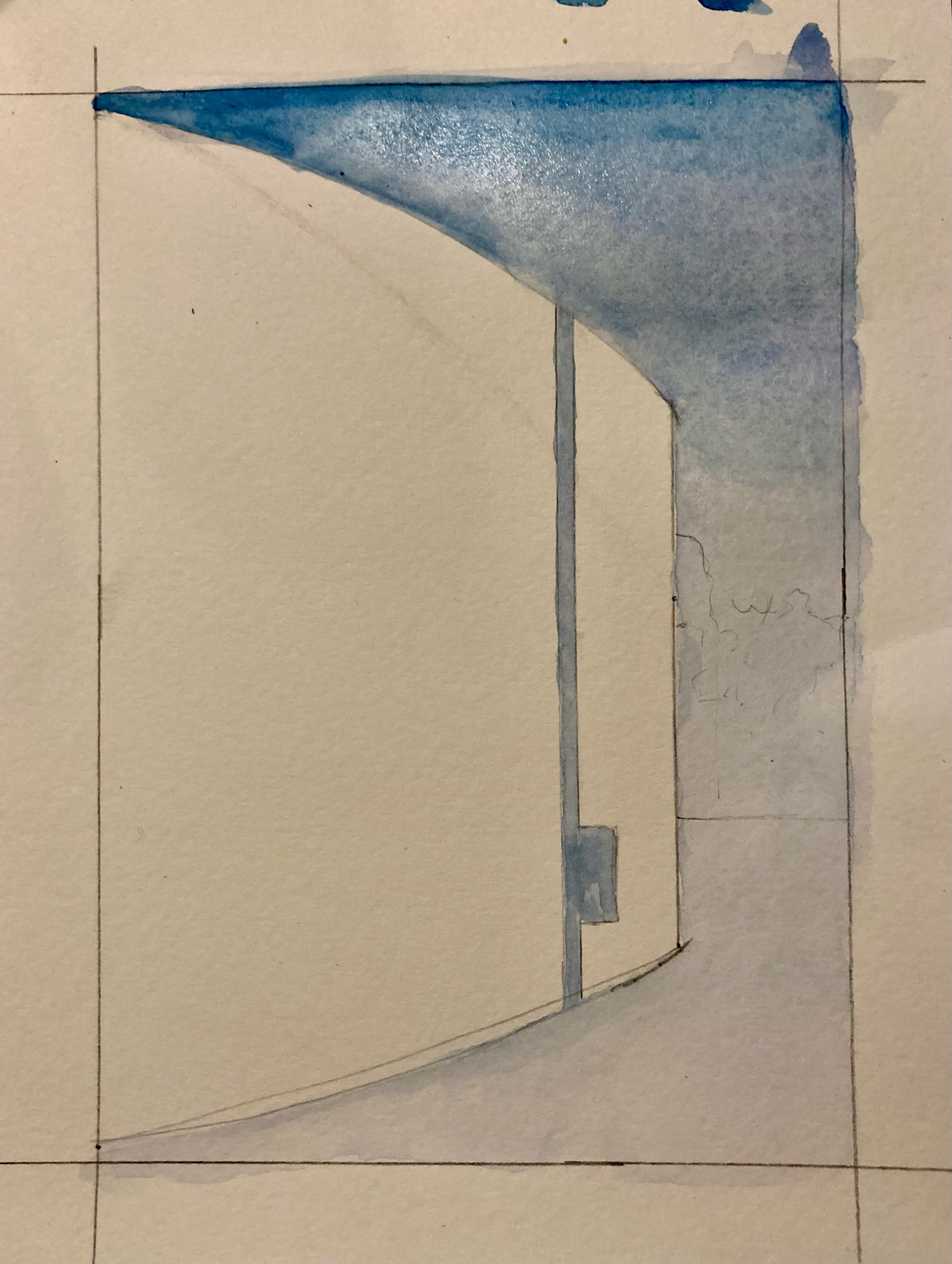

Watercolor Studies

Race Cards

Maya Lin, the famed designer of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, wrote the following in her book Boundaries in a chapter titled “Existing Outside.” It continues to be relevant…

Sometimes a total stranger - a cabdriver, for example - will ask me where I am from. I mutter, “Here it goes again” or I will respond “Ohio,” and the stranger will say, “No, no, where are you really from?” It used to upset me to always be seen as other - not really from here…not really American…but then from where? So I used to practically get into brawls with the person, insisting I was really from Ohio. At that point, more than a few have lectured me on how I shouldn’t be ashamed of my heritage. So now, practiced at avoiding conflict, I say, “Ohio…but my mother is from Shanghai and my father is from Beijing.”

The questioner generally seems satisfied.

But the question, however innocently it is asked, reveals an attitude in which I am left acutely aware of how, to some, I am not allowed to be from here; to some, I am not really an American.

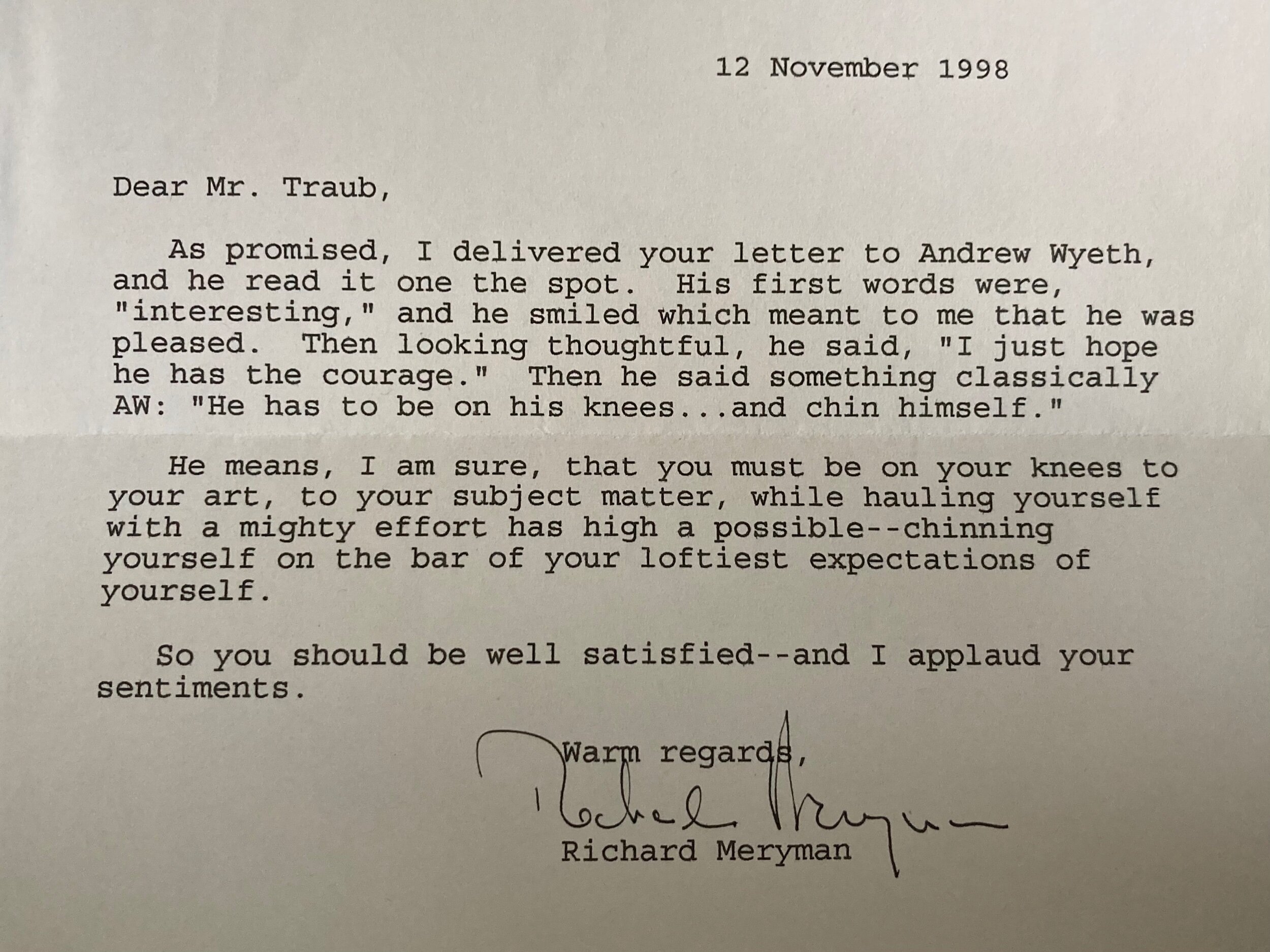

"Knees & Chin"

He has to be on his knees…and chin himself.

Those are the words relayed to me from Andrew Wyeth through one of his biographers, Richard Meryman, back in 1998. As I was finishing college with a broad-based fine art degree, I began to intensely study the life and work of Mr. Wyeth. After graduating I read Meryman’s biography Andrew Wyeth: A Secret Life, which led to my writing to the artist himself, the story of which I’ll come back to a bit later…

…In the meantime, I will admit that my interest in Wyeth bordered on an obsession. It started at some point with viewing perhaps his most famous painting, “Christina’s World,” in several books (to this day I’ve yet to see the painting in person) and for all it’s “realism” (for which Wyeth was both praised and criticized by his contemporaries) is as “surreal” a work of art as anything labeled such. In fact, I would contend that it may be more surreal. Because, you see, for all the narrative back-story, the masterful egg tempera techniques, and the lovely yet altogether discomforting pose of the figure, there’s still something “off” about the composition, the work succeeds by transporting the viewer further into the subconscious. I should add, however, that I don’t mean to force his work into that category, but it is how I’ve interacted with it. Perhaps a better way of framing it is as a “concrete surrealism” that draws out the glory of everyday things. Which is why the criticisms leveled against his work as “sentimental” or “photorealist” annoy me. You really must let it interpret you.

Spend any amount of time meditating on Wyeth’s iconic works, and you begin to see this visual-off-ness that pushes the work beyond strict realism for realism’s sake. From his “Winter 1946” to “Marriage" to the haunting “Adrift” or “Pentecost” there’s always a piece of the perspective and the modeling that defies the notion of a pretty picture. And therein lies Andrew Wyeth’s brilliance: he created works that are never flawless but they are perfect. He took that thing that looks real (which it is) and yet invites us to see both that thing or person and something more.

Even if I had never known about the story of Christina Olsen from the books about the painting, “Christina’s World” captivates because as you allow it to simply be and interpret you (the viewer) the not-flawless-yet-perfect visual story unnerves and delights. The contorted figure struggles toward a home, one that may or not feel like a home. The house itself sits awkwardly right on top of the horizon line. The two-track partially hinted at is no where near the lonely figure, which further alienates the subject. The faded pink of Christina’s dress contrasts (flawlessly in this particular case) with the overwhelming earth-tones of the rest of the composition which hints at the presence of life in a place that may be struggling to stay alive. There is more, of course, but the depth of this work would never have been accomplished had the artist sought to paint the scene exactly as it looks in real life.

At this point I ought to get back to the topic of this essay. However, a few words about who Richard Meryman was. The highlights are that he was a longtime journalist for Life magazine whose well known for having published an interview with Marilyn Monroe just two days before she passed away. He interviewed a wide-array of entertainers and celebrities. Should you do a search of his name online, you will find plenty of information about his life and work. From my understanding, he and Andrew Wyeth were considerably close which was apparent to me, at least, as I read his book. To be certain, one’s life isn’t simply a list of bullet points, and I expect there’s so much more that includes joy and sorrow that is Richard Meryman. My tale here certainly demonstrates a legacy of kindness and generosity even to a stranger using him as a “mediator” to someone else.

I wrote this letter to Andrew Wyeth in 1998. Handwritten, no copies, so no archive of it other than (perhaps but most likely not…and that’s okay) in some box buried at the Wyeth estate. All I have are the short notes sent to me from Richard Meryman that will have to suffice. I’m pretty sure I thanked Wyeth for his work and impact on my own life and work. I was particularly fascinated by the lifelong discipline it took to become a master of his craft, a discipline that I can only imagine even in my own practice. For it is clear he was just that, a master. I also celebrated his commitment to “realism” in the face of other abstract expressionist work that had grown in popularity during his lifetime. All those things I’m sure I addressed in my letter.

To be honest, though, I doubted I would ever hear anything back. So it was a surprise to receive the following letter from Mr. Meryman (I had written to him through the HarperCollins address) within a couple weeks! It read:

Dear Edward Traub -

As you see, I have received your letter and your wonderful, (moving) sentiments. I am going down to see Wyeth next week and will deliver your letter by hand. I know he will be very touched and pleased -

Richard Meryman

I was ecstatic, of course, and content with that. I had no expectation of further correspondence. But again, I was mistaken. In a few short days I received another note from Mr. Meryman dated “12 November 1998”:

Dear Mr. Traub,

As promised, I delivered your letter to Andrew Wyeth, and he read it on the spot. His first words were, “interesting,” and he smiled which mean to me that he was pleased. Then looking thoughtful, he said, “I just hope he has the courage.” Then he said something classically AW: “He has to be on his knees…and chin himself.”

He means, I am sure, that you must be on your knees to your art, to your subject matter, while hauling yourself with a mighty effort (as) high (as) possible — chinning yourself on the bar of your loftiest expectations of yourself.

So you should be well satisfied — and I applaud your sentiments.

Warm regards,

Richard Meryman

Years later I still read these letters with delight and with a sense of calling. My wife and I have discussed these words a number of times, and I have yet to find a clearer way to describe my approach to life and work. As an artist, it is with some trepidation that I confess my waywardness in such a commitment to my art. I am a polymath, easily moved from one discipline to the next (something I try to embrace as a strength…which it can be) and my painting style has been at times lacking in focus. Those who know me and my paintings will probably be surprised to associate Wyeth with having impacted my work. However, another friend did describe my work as a cross between Andrew Wyeth and Mark Rothko; a humbling yet somewhat accurate description.

For years I sought to work, and taught others to work, at least as a starting point, from some level of “realism,” which I consider a deep attentiveness to what “is” and then from there an artist can branch out. Until one participates in this deep practice in careful observation, they can never authentically move abstractly. I credit my friend and distant mentor, Makoto Fujimura, for guiding me in my coming to grips with realism and abstraction and so I journey on in waves of productivity and dryness.

He has to be on his knees…and chin himself.

I’m grateful for these words. I’m still amazed that Andrew Wyeth read my letter. Sometimes I wonder what it would be like to have met him in person; and yet this tale suffices perhaps more powerfully to demonstrate that even the simplest interaction can shape someone’s life for going on twenty years now.

As profound as the words Wyeth spoke are, this essay is also a tribute to Mr. Meryman. He didn’t have to do what he did, and yet he considered it important enough to deliver my letter in person. He encouraged this artist by allowing me an opportunity to encourage another (albeit a “famous” artist). Wyeth’s words echo daily in my work, no matter what or where, as I explore things that are important to me, to kneel down in order to understand my subject, be it cultural and societal issues ranging from racism to farming, to my own art practice and life with my family. There will always be that tension between submission and effort. The work (“chinning”) is the part that can be the most vulnerable. These things are what Andrew Wyeth called out in me.

Postscript: through the (sometimes) wonderful world of social media I have recently reached out to Mr. Wyeth’s only grandchild, Victoria Browning Wyeth, who encouraged me to write this. She is passionate about her family’s work and sharing it with the world. Many thanks to her.

[Thanks for reading. Please feel free to join me here, but also promise to read and engage thoughtfully and with a generative spirit keen on cultivating a better world along the way.]

Let Us Live Without Hope

A Poem by Wendell Berry

III.

Yes, though hope is our duty

let us live a while without it

to show ourselves we can.

Let us see that, without hope,

we still are well. Let hopelessness

shrink us to our proper size.

Without it we are half as large

as yesterday, and the world

is twice as large. My small

place grows immense as I walk

upon it without hope.

Our springtime rue anemones

as I walk among them, hoping

not even to live, are beautiful

as Eden, and I their kinsman

am immortal in their moment.

Out of charity let us pray

for the great ones of politics

and war, the intellectuals,

scientists, and advisors,

the golden industrialists,

the CEO’s, that they too

may wake to a day without hope

that in their smallness they

may know the greatness of the Earth

and Heaven by which they so far

live, that they may see

themselves in their enemies,

and from their great wants fallen

know the small immortal

joys of beasts and birds.

"Essence de l'eau"

Of What He Cannot Do

I picked up a new copy of Annie Dillard's Holy The Firm to read a second time. Here is what I read today and it has brought a deep pause (breath!) to my day:

“We do need reminding, not of what God can do, but of what he cannot do, or will not, which is to catch time in its free fall and stick a nickel’s worth of sense into our days. And we need reminding of what time can do, must only do; churn out enormity at random and beat it, with God’s blessing, into our heads: that we are created, created, sojourners in a land we did not make, a land with no meaning of itself and no meaning we can make for it alone. Who are we to demand explanations of God? (And what monsters of perfection should we be if we did not?) We forget ourselves, picknicking; we forget where we are. There is not such thing as a freak accident. “God is at home,” says Meister Eckhart, “We are in the far country.”

We are most deeply asleep at the switch when we fancy we control any switches at all.”

I'm going to let that linger for a while.

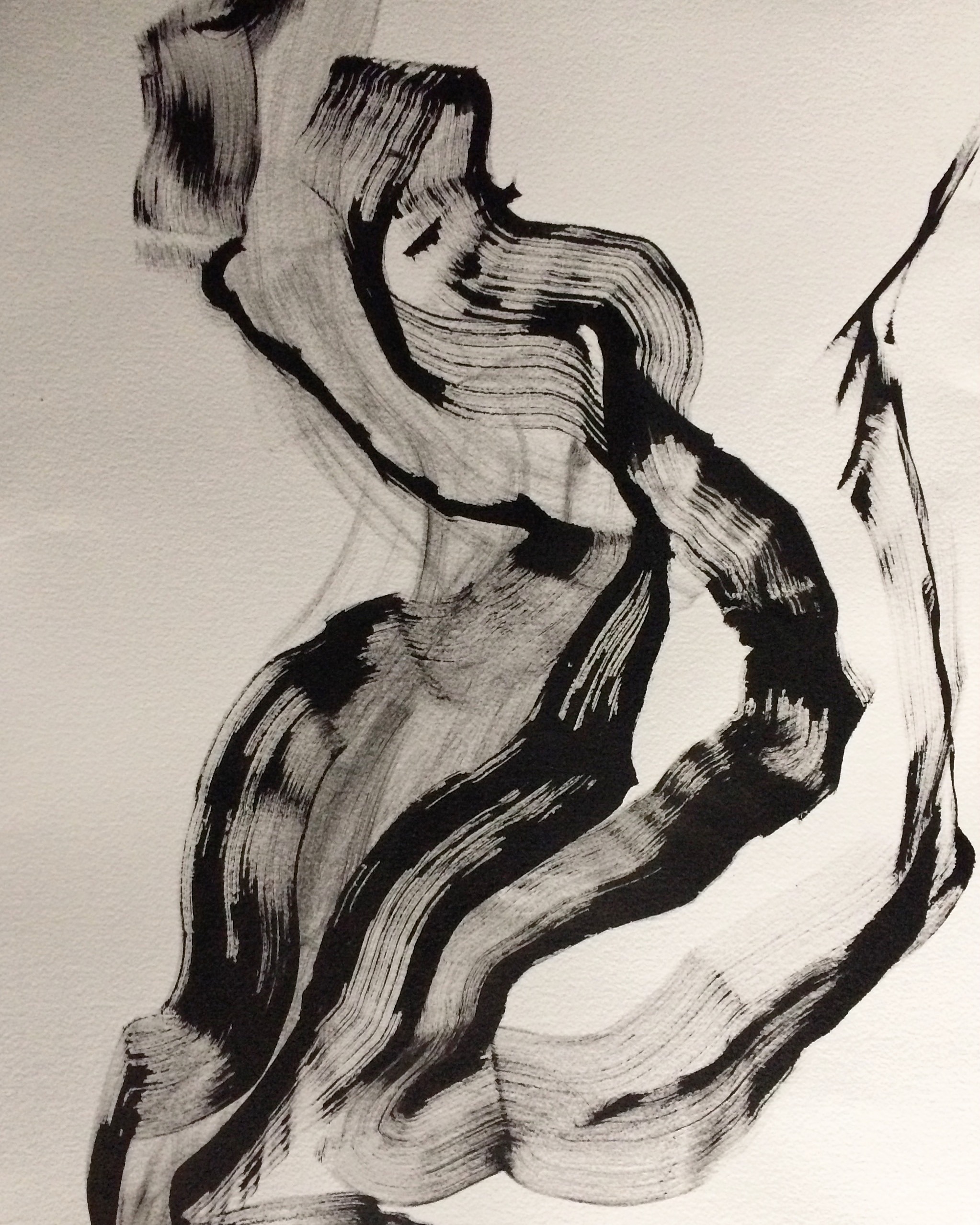

simplicity

simplicity

form

ink

paper

body

figurative

absence

presence

Commoners: Barber Bruce

““Commoner” isn’t a dirty word here; it is a thing to be proud of. It means you have rights to something of value, that you contribute to the management of the fells, and that you take part in our way of life as an equal with the other farmers. If you farm Herdwick or Swaledale sheep and they are hefted to the common grazing land on the fells, then you, by definition, often belong to an association of commoners. (1)””

The following is a slightly edited version of a piece I wrote for my hometown newspaper, The Piatt County Journal-Republican, in Monticello, Illinois. It's actually part two of my "Commoners" series.

Bruce Jordan (photo courtesy of the Champaign-Urbana News Gazette) (2)

“But it’s a fact that knowledge comes to barbers, just as stray cats come to milking barns (3).”

I don’t have much hair to cut. I used to wonder why a bald man like my own dad would pay money to have a barber trim what little was left. Seemed like there should have been a “bald-guy” discount. That’s another topic for another time, and all economics aside, it was just a few years ago when I was home visiting my parents in Monticello, building a deck on the front of the house, when I decided to be that bald guy who goes in for that haircut. It was so hot that week in July that it made sense as well to seek a respite from the midday heat and stop in to see Barber Bruce.

My haircut is pretty simple. I have even taken on the duties to cut my hair all by myself, and with the exception of asking one of my daughters to “check the back” of my head for anyplace I missed, have been using that old Wahl razor to trim to near shaved status. I guess I’m grateful that being bald, and shaving most of one’s hair off is sort of on-trend. Many a balding male has now sought to alleviate the torture of the hair-on-the-sides look by simply going with a more bad-ass shaved head look. Most of us have done so all the while allowing facial hair to grow in the form of a beard or goatee; there aren’t many heads completely void of hair somewhere.

That day in July, though, I went to see Barber Bruce Jordan. The Champaign-Urbana News Gazette published in 2014 an article about “Hair Jordan” and memories rushed into my mind, and a life that seemed so far gone for me all of a sudden became vivid again. I knew Bruce had been at it a long time, but fifty years? He still remembered who I was that day in July (and I hadn’t been in his shop for almost twenty years) in part because I look a lot like my dad and my dad knows Bruce pretty well and will occasionally stop in too. It’s as if the only way he doesn’t know your name or who you belong to is if he had never met you. That’s a wordy way of saying the Barber of Monticello has a long memory in the best possible way.

Bruce's work and life are an authentic example of what a true "commoner" is. As I mentioned in my previous commoners post a few weeks ago, it is my intention to help us become more common, not less. In the spirit of James Rebanks' book The Shepherd's Life.

I would go to his shop regularly as a high school student. Our coaches wouldn’t allow us to have long hair, so it was important to keep it clean. Bruce would ask about how things were going in whatever sport I was playing at the time and I could tell him. Our family also attended the same church as the Jordan’s, which gave us some other topics. He seemed genuinely interested in my story and he had a presence that made me want to make him proud of whatever it was that I did in life. I kept my hair short.

But one day I was waiting for my haircut and one man ahead of me got up for his turn in the chair. I don’t think Bruce knew him, but he could tell (as I could, too) that the guy was in the military. Anyone who knows him, knows that Bruce’s stories are 100 to 1 when it comes to his two years in the army compared to anything else (except maybe his wife, Linda). It was at that moment that I learned the phrase “high-and-tight.” Bruce simply said right away, “High and tight?” And the man said, “Yep!” Anyone in the Army knew what that meant. For men, it’s the only option while in active service. Some call it a “crew cut” but I don’t think that quite fits the billing, it’s a tad too civilian. And so in that moment it became clear that Bruce and this gentleman had a connection. It was as if Bruce had just saluted the guy and they were instantly conversant, with Bruce showing a unique empathy and care for what his customer was about to embark upon (active service, not the haircut). I didn’t have words for it then, but in retrospect I was watching the art of connection lived out in the most glorious and unpretentious ways.

Bruce’s shop window is adorned primarily with a manually set dial, reminiscent of Wrigley Field’s manually run scoreboard (a comparison I’m pretty sure Bruce will appreciate as a die-hard fan of the Chicago Cubs), announcing to those who walk or drive by how many customers are waiting for a haircut. There are no appointments which, I’ll admit, could make it difficult if you’re on a tight schedule. But maybe that’s the larger point to my essay. What Jordan’s Barber Shop is is a vital connection to, and functioning reminder of, the most important things: and it has little to do with aesthetics.

Or maybe it does have something to do with aesthetics. Businesses and the commoners who “run” them in this way epitomize the aesthetics of community. Bruce does this through the art of storytelling. That summer visit reminded me again about the reality of Bruce’s craft. There is never a topic or story he cannot converse about. Some people are incapable of doing this in a way that doesn’t become a competition of “one-upmanship.” Thankfully, Bruce is not in that category. His stories are inclusive and playful, even if the topic is difficult. And although “politics” may not be discussed much, if at all according to the News-Gazette article, Bruce will not hold back if there’s an issue he’s convicted about.

The beauty of community and the art of storytelling is what is vital to the commoner life.

After I re-read the article recently, I was immediately reminded of Wendell Berry’s novel Jayber Crow. Jayber, a commoner as well, is a barber in the tiny fictional community known as Port William. I will not belittle Berry’s work or Barber Bruce’s life by making it seem as if Jayber Crow’s story matches Bruce’s in every and exactly the same way, but the fact that Crow is a barber certainly helps. More to the point is that barbers, and others whose work is “small,” are actually the heroes in any community. Today, to say something is “small” is considered “less than” those things that are “big.” While I (and many others I grew up with) moved on to become somehow great, to exceed the small expectations of our communities, many others have stayed. To stay or leave one’s home place is neither good or bad, and depends on the individual’s life circumstances and talents, but Bruce is one who has stayed and been a grounded archivist of the Monticello community. The “bigger is better” mindset is a myth.

Earlier in his life, Jayber Crow had goals of being a pastor which would have set him up as a “big” person in places like Port William. In the end he remained “small” in Port William, observing the town change over decades and thus taking on a “priestly” role in spite of himself. Jayber says:

I don’t mean for you to believe that even barbers ever know the whole story. But it’s a fact that knowledge comes to barbers, just as stray cats come to milking barns. If you are a barber and you stay in one place long enough, eventually you will know the outlines of a lot of stories, and you will see how the bits and pieces of knowledge fit in. Anything you know about, there is a fair chance you will sooner or later know more about. You will never get the outlines filled in completely, but as I say, knowledge will come. You don’t have to ask. In fact, I have been pretty scrupulous about not asking. If a matter is none of my business, I ask nothing and tell nothing. And yet I am amazed at what I have come to know, and how much. (4)

It seems to me that this is an accurate account of the true role Bruce lives in my hometown. He’s a mediator. Better yet, he’s an advocate. He’s someone who listens and speaks in ways that have brought life to the community simply by being present and doing good work.

Rebanks, James. The Shepherd's Life: Modern Dispatches from an Ancient Landscape. New York: Flatiron Books, 2015. p. 23. Rebanks regular uses the word "fell" or "fells" as a noun referring to what is known in Northern England as a "hill or stretch of high moorland" (Google search).

Photo from http://static.news-gazette.com/sites/all/files/imagecache/300_width_scale/images/2014/06/05/Barber.jpeg

Berry, Wendell. Jayber Crow: A Novel. Berkeley: Counterpoint, 2000. p. 94.

Ibid.

I dream of a quiet man...

“I dream of a quiet man

who explains nothing and defends

nothing but only knows

where the rarest wildflowers

are blooming, and who goes,

and finds that he is smiling

not by his own will.”

Wendell Berry

It Is Good to be a Sage: Fall, Football, & Fidelity

“The people that once bestowed commands, consulships, legions, and all else, now concerns itself no more, and longs eagerly for just two things - bread and circuses!”

“Winning is not the purpose, but it is the point.”

The ancient Roman satirist Juvenal (c. 55-127 AD) lamented the way in which Roman citizens abdicated their civic and cultural responsibilities for “bread and circuses.” It was the Plebeians, or working class, who were kept from rising up against emperor Augustus through a state policy of free spectacles like the gladiator games and cheap food. At it’s worst, sports in our society borders on that type of pacifying activity. We have entire television stations devoted to sports, and whole sections in our newspapers. The Super Bowl is virtually a national holiday, and let’s not even get into the insane salaries some professional athletes are paid. These are the realities that bother me about our over-emphasis on sports, and the similarities to ancient Rome are food for thought. On top of that are the realities outside of the sports scene all over the world where lives are hanging in the balance. These brutal and humbling realities should remind us that sports fans and athletes may use language of warfare in preparation to face an opponent, but playing a sport is not a true “war” nor is the opponent our true “enemy.”

I loved Friday nights and Saturday afternoons as a football player at Monticello, though. During pre-game it was the smell of that grass as I stretched out on the ground with the rest of the team, or the calm and quiet we experienced as quarterbacks warming up long before others came out to get ready. I also remember the smell of the gear and the usually ill-fitting practice uniforms we had to wear during “two-a-days” which seemed to go on forever. I remember during my years playing at Monticello and falling in love with our game-field. Our home field is still one of the coolest places ever had the privilege to play.

With Moore Gym looming over the field on the north end and no track between the sidelines and the bleachers our field had a small, stadium-like atmosphere. The energy was unmatched, especially during playoffs.

During my years there were bleachers set up at the north end as well and younger kids were always watching the game from there...or socializing, whatever the case may be. When I was in “middle school” at White Heath there were arm-wrestling contests between the kids from White Heath and Monticello in those bleachers. It was a rite of passage. I remember arm-wrestling Tony Galbo, and I think I won but I’m not sure, you’d have to ask him sometime. No matter what happens in the future of Monticello’s facilities I hope varsity football games will always be played there. To move from that field would be as tragic as the Cubs not playing at Wrigley Field anymore.

Our head coach was Hud Venerable. John Beccue (who later became head coach and had a ton of success) was our defensive guru. The other assistants were Kyle Ness, Larry Albaugh, Butch Sawlaw, and Brad Auten. I looked up the word “venerable” a few years after I graduated because I kept hearing it used in other contexts. It means “someone accorded deep respect because of age, wisdom, and character.” I’m fascinated by that name, it defined Hud, and it (to me) defined the program for his time there; and it remains over the Sages football tradition. Everything was about excellence and that sense of honor. One of the hardest hits I ever took during my 8 years of football came from Coach Beccue himself. It was during practice when he demonstrated a technique on me, but it did not feel like a “demonstration.” It hurt! That was the mentality that permeated Sages football.

Another deep-seeded memory from my era was the attention to detail and perfection Hud instilled in every aspect of our game. There was one practice when the offense was breaking from their huddles and sauntering to the line of scrimmage. No urgency was expressed, zero energy. Coach Venerable became as angry as I had ever seen him about the lack of “it” that he lit into the offensive units and made us practice the “break!” If my memory serves me correctly, we spent what seemed like a half-an-hour breaking from the huddle the right way, and that’s a ton of time in a 2 hour practice. To this day, when I watch football I become so frustrated when I see offenses “saunter” to the line. It drives me nuts when players “walk” onto the field of play in general, no matter what the sport: soccer, football, lacrosse, etc. For Coach Venerable, and now for me, it was all about readiness and enthusiasm.

Coach Venerable had a look of intensity, he walked with purpose, and you couldn’t help but want to play for him. Even with that “intensity” he often sported a grin that would accompany his confidence in what we were out to accomplish. I wouldn’t call it “cockiness” but an air of confidence and, even better, joy, at the prospect of playing another day. Contrast that intensity with a crazy-striped-winter hat complete with a fuzzy ball on top during extra cold games, and you get the picture of Hud. Serious, with that glorious playfulness thrown in almost against his will. He reminded us that if he wasn’t on our case then there was a problem, he cared and therefore he pushed us. He was never abusive, but he made us envision success. And then, for me, there were also those glorious moments when you would see into his world outside of football when he’d have players over to his house for a meal, or when he chaperoned the prom dance.

I’ll never forget the Monday after a particularly hard game for me when I was a sophomore. I’ll admit that I didn’t fully understand how to “play” football early on and he called me out during halftime when I sort of “danced” around a tackle and in turn missed it (turns out that’s an important part of the game!). Anyway, that next Monday, after P.E. class (he was my teacher), he put his arm around me and checked to make sure I was doing ok. You see, the best teachers and mentors really do love their students.

We enjoyed a great deal of success (four straight undefeated regular seasons, one quarterfinal and three semifinal appearances). We never got to that coveted State Championship, but we had a ton of fun and started a tradition that I believe still influences Monticello football. There’s nothing like those late nights riding the buses home from a far-off playoff game in “nowhere” places with a hundred cars following, and then being greeted by our families and friends at the school celebrating the delight of a win. If you’ve seen the movie Hoosiers you will remember the scenes of the cars lined up behind their team’s bus. It was like that. In fact, I happened to be home last year after the MHS Boys Cross-Country team returned from their state championship! Again, a convoy of fans, car horns sounding off, and sheer delight in our school’s first team title. That was no small feat and no matter what sport our kids may play, as a community those are things to celebrate.

I could tell dozens more stories and so could many of my former teammates. But what stands out to me is the image of community. There was an authentic feeling that we were actually playing for our hometown.

The importance of this cannot be overstated. Where my family currently lives there is a whole “club” system for most of the sports, and although there’s a great benefit for kids honing their craft as players and that in turn helps the school teams, what it can and sometimes does create is a division between kids who do and kids who do not play for a “club.” Further still, it can at times lessen the significant role school sports play in any community. To their credit, Coach Venerable and Coach Bob Trimble (our basketball coach, who I’ll write about as hoops season approaches) always encouraged us to play multiple sports because it wasn’t just about their sport but about the community.

My son has played Lacrosse the last few years and like other sports there’s an entire system for kids to play during the off-season. One of the other purposes of the club system is to give kids exposure to college coaches. I said to one dad of my son’s teammate last Spring how much I appreciated the way his son played under great pressure. I asked this dad if his son was easily rattled and how he generally handled the pressure of his position as goalie. He said to me, “he really doesn’t feel much pressure in these games, there aren’t any college coaches watching these games anyway.” Now this may not be the attitude of all families, but it is telling. This young man is a great player on our school team, in fact he broke some school and state records for saves, but the mentality of the team and school’s program being insignificant is telling.

I played three sports at Monticello High School and then went to Taylor University where I competed in two. Now that my oldest two kids are in high school this year, I’ve begun once again to reflect on what playing sports is all about hopefully in a non-living-vicariously-through-my-children sort of way. Ultimately, it is about community. To play for your hometown, be it Monticello, Grand Haven, wherever, it is a privilege. Coach Venerable said that to us on day-one of my freshman year. He said what we were doing is a privilege. It didn’t make us better than other people in our school, but it is a deep honor to be a part of a group working together for the purpose of representing our community in the best possible way. I had never heard of playing a sport as a “privilege” before that day; and as you can tell, it shaped me ever since.

But let’s be honest here. Winning makes it even more fun.

During my sophomore year we went to play St. Teresa in Decatur. The game was highly anticipated that week because both our teams were at the top of our conference and looked to play deep into the playoffs. St. T was known for their size and athleticism and Monticello, well, was not.

Don’t get me wrong, we had great athletes who made a huge impact like the farm-strong John Lieb (whose son is on the current team), but what made our team truly go were the generally unheralded “small” lineman who didn’t look like “lineman.” Stan Johnson in particular was one of those guys. One could have made the case that he was one of the smallest players on our team, but what I remember about Stan was him running off the field after a score where he once again surprised and dominated his opponent (wearing those classic padded gloves) yelling, “I LOVE THIS!”

Anyway, back to the game at St. Teresa. I was more nervous than usual that night and I wasn’t even a starter. I remember when we first ran single file out onto the field as a whole team and I was running behind Ryan Perry, another player like Stan (padded gloves and all), who exceeded all his limits as a lineman and made the team go. What I heard as we came onto the field were a bunch of folks on the St. Teresa side literally laughing at us! Comments regarding our stature and competence flew, and I do think I wondered for at least a moment if it might be true.

None of that was true. We won in convincing fashion.

Although winning isn’t the purpose, it is the point.

It’s amazing, for me anyway, that although most of my life has now been spent outside of Monticello, those memories remain vivid. Now in the Facebook World especially I’ve awakened to the truth that what truly mattered in all this was the people. I may not have seen someone for 20+ years, but I still care about them. I’m still moved and saddened when I hear about deaths, divorces, life-threatening accidents, that classmates and teammates experience. I’m also moved to see photos of friends’ kids now in high school as well, and then realize how time really does move quickly.

Juvenal was right to call out his fellow citizens and warn them of the complacency that accompanied the gladiator games with their cheap food and entertainment. Our society has certainly taken things too far with our obsession with sports. However, what we learn by playing sports for our hometowns and communities has to do with fidelity. Fidelity to the reality of our connections to others for whom we play. We train in the off season because we care about what we will be doing during the season, even when game days are far off. We endure the mundane with the hope that there will be moments in the future when what we have chosen to do, the people we have chosen to do it for, and our deepest desires for delight are one and the same.

This fidelity manifests itself in our adult lives. As frustrating as it is, it’s in how we handle adversity and suffering and loss that we learn the most about ourselves and how to relate to others, and sports is one experiential “classroom” where kids get to learn some of those vital lessons. Several years ago, Ryan Dyson had a horrendous accident that nearly took his life, he’s survived and persevered in heroic ways consistent with what I always knew of him since the 1st grade. He now has a son who is a student-athlete at Monticello and some of those traditions and lessons are finding ways to breathe life into the current generation.

Tony Galbo and his wife Liz, as most in Monticello are aware, lost their 5-year-old daughter, Gabby, through a series of events that no one can explain or rationalize. Not everyone survives such a loss, and I know Tony might argue that he’s not “surviving” very well but he’s still there for his family especially. Now on top of that, they have persevered on behalf of other families with their work in passing “Gabby’s Law.” Tony and Liz will never be done mourning their loss, and they should not be expected to do so either. What made Tony a great teammate wasn’t just his blocking as our center, but his absolute loyalty (his fidelity) to his teammates, and it is this same loyalty that won’t allow Gabby’s life to be forgotten or for the rest of his family to be left alone.

These stories are what playing for your hometown is all about. When we know our “neighbors” we will do anything for them, even those who we don’t normally get along with. The “life-microcosm” of sports like football is one place where some of us were allowed the privilege of learning those things. I’m amazed at how powerful these truths are for me, even as I live in another state.

I don’t know Monticello’s current head coach, Cullen Welter, but I’ve been following Sages football from wherever I’ve lived. So far this season looks like another great one! I know that the traditions I experienced remain in part, plus a Twitter account! [@SagesFootball] I know we’ve been on the verge of some great things and I’m hopeful the team this year will take that next step and complete the task that even all our great teams could not accomplish. My senior season, sadly, we did not make the playoffs. All four years of my college career I never had a winning season either. I have experienced lows and highs. But no matter what, autumn still brings about another season of anticipation of success for a bunch of boys committed to each other and their hometown. I like to think Juvenal would enjoy watching games at Monticello for this very reason.

"Driftwood Time" - Dismembering/Remembering

A while back I wrote about one of my favorite old paintings titled "Driftwood Time" which was painted around 1998-99. In the blog post I mentioned that I intended to cut the oil painting (which is on a scrap piece of particle board usually used for construction) into multiple smaller works. Well, I did just that.

Pictured here are the 12 remaining sections. The visual effect is intriguing and playful. Each square can be turned any direction I hope you'll enjoy.

As always, each square is available for purchase at the Store where you can quickly and easily click the badge above each individual piece.

Commoners

““Commoner” isn’t a dirty word here; it is a thing to be proud of. It means you have rights to something of value, that you contribute to the management of the fells, and that you take part in our way of life as an equal with the other farmers. If you farm Herdwick or Swaledale sheep and they are hefted to the common grazing land on the fells, then you, by definition, often belong to an association of commoners. (1)”

James Rebanks (center)

I know little to nothing about sheep or the work of a shepherd. In fact, I've heard more jokes about the lifestyle than I know the truth. However, it is one type of agriculture, and my interest in all-things-agricultural compelled me to pick up this incredible book by James Rebanks titled The Shepherd's Life: Modern Dispatches from an Ancient Landscape. Rebanks book is both a detailed peek into the sheep and shepherd culture of what is called the "Lake District" of England as well as the author's memoir of growing up in the ancient lineage of shepherds. What intrigued me about the book before reading it, was the dust jacket describing Rebanks' story of what it means to be from a particular place and choosing to remain in the place. It is a story of his ongoing journey to stay.

My interest in the effects, and particularly the benefits, of livestock grazing on our land(s) drives me in many ways to learn from every source at my disposal. I was looking through the "biography" section at our local independent bookstore, The Bookman, when I found it. I hadn't heard of Rebanks or his book. I was looking to purchase one of Michael Perry's books. If you've not read Perry, you're missing out. The man's stories make me laugh out loud, a much needed remedy in the face of my seemingly incessant melancholy (if you shuffled through the music on my iPhone you would understand what I mean). Yet, Perry's humor brings with it a dose of grace in truth-telling as the following excerpt demonstrates:

“In the world of the certifiable stoic, the repression of emotion is just the more obvious half of the battle. The rest of your time is consumed with masking even the appearance of the existence of desire. Anyone can hold back a tear or dodge a hug - it takes a real hardcore Norwegian bachelor to pretend you don’t want a cookie. If I were commissioned to design the official crest for the descendants of emotionally muzzled Vikings everywhere, it would begin by looking up the Latin phrase for “No thanks, I’m fine.”

This outgrowth of the neurosis turns the simplest trip to the grocery store into a pulsating gauntlet of dread. Shopping for staples seems benign enough, but when you present your basket a the counter, you are revealing something deeply personal about yourself. Your are approaching a stranger and saying - in public - “this is what I desire.” And not only that, “this is what I desire to put inside me.” If you are buying a battery cable or a snow shovel at Farm & Fleet, there is no shame. These are exogenous needs. Gotta start the car, gotta clear the sidewalk. But with food, there are distressing elements of psychosexuality in play - Appetites! Hungering! Orality! Gimme Twinkies! - coupled with the implication that if you ingest you must surely excrete, and this not a place the stoic wants to, um, go. (3)”

However, the irony of my search for a book by Perry, who lives and works in rural Wisconsin, leading me to A Shepherd's Life is, in retrospect, more than coincidental. You see, both men now live where they grew up. Both journeyed for a season into other places, but both somehow knew they would end up "home" and finally have.

To say these authors' stories are alike is helpful, but it would be a disservice to imply that they are identical. The big picture view, however is that they both address the presence and absolute necessity of the "commoner." Perry delightfully reminds of the significance of place in talking about small-town watertowers:

““Here we are,” say water towers on behalf of a community, “and this says something about us.”

...More than the houses, more than the streets, more than the small green sign at the outskirts, it has always been the sight of the water tower that has told us, “here you are.” (4)”

I'm thrilled by Rebanks' quote at the beginning of this essay, defining what a true "commoner" is. I think most, especially here in the US, think of the commoner as some kind of lower-life-form of society. There is the "ruling class" and then there's the "commoner." What Rebanks is attempting to do is reclaim the term for what it truly is from within the particular context of his own story. Its akin to Wendell Berry's words in numerous places affirming the interconnectedness (better still, the interdependence) of all of life. In fact, it is this interdependence that pushes our language further than the commoner being simply utilitarian, and instead breathes life into the reality of mutuality among members of any community.

We are all commoners.

My friend Makoto Fujimura approaches these themes from the perspective of "culture care." (5) Instead of waging culture "wars," we are called to be a generative presence in our communities. Regardless of whether or not we live where we came from is besides the point. We are all commoners, and therefore we are part of the ecosystem of the culture in which we live. Most of us, though, haven't taken the time to listen well to the place we live. Gone are most, if not all, "native" traditions and practices. Yet we still remain dependent upon each other for everything, even if we have never met the source of our sustenance. Rebanks, also now a consultant with UNESCO, writes:

“[W]hen local traditional farming systems disappear, communities become more and more reliant upon industrial commodity food products being transported long distances to them, with all the environmental cost (and cultural disconnection from the land) that entails. They begin to lose the traditional skills that made those places habitable in the first place, making them vulnerable in a future that may not be the same as the present. No one who works in this landscape romanticizes it. (6)”

Rebanks, then, affirms the necessity of connection. Unfortunately our culture has sought to grow and "heal" by becoming more autonomous instead of more connected. Wendell Berry writes:

“The fashionable cure [for the disease of disconnection]...is ‘autonomy,’ another illusory condition, suggesting that the self can be self-determining and independent without regard for any determining circumstance or any of the obvious dependences...The “cure” thus preserves the disease. (7)”

We cannot live as commoners if we seek to live autonomously. We can pull our selves up by our bootstraps only so far, we still need someone to craft the boots. Writing from my own mid-west American context I can say that autonomy is the virtue of virtues. Craftspeople or carpenters, like me, have to continually defend our work and seek to justify our prices in order to make a viable living. Sometimes it feels as if it is forgotten that those who have "good" jobs working for larger companies still have to make a profit and that is dependent on others who do the work and those who purchase the goods or services with little concern over the markup for profit. Generally speaking, the larger the company the further the distance becomes between the consumer and the producer.

And for some reason we question less the large company because that's just the way it is and they're too big. The problem, then, is that as soon as we start to say, "Well that's just the way things are," then we've given in to a sense of powerlessness that will hinder real growth and health within our society. Our imaginations become limited, and we lay down for the empires around us. True freedom from empires of unending consumption, ironically, is accomplished through the healthy and porous "boundaries" of the commoner's existence. For Rebanks, his life on the fells of the Lake District, exemplifies just such a freedom:

“Ours is a rooted and local kind of freedom tied to working common land, the freedom of the commoner, a community-based relationship with land. By remaining in a place, working on it, and paying my dues, I am entitled to a share in the commonwealth. (8)”

And so Mr. Rebanks, along with Michael Perry and others, has propelled me to write about what it means for us to become more "common," not less. So some of my upcoming posts will deal directly with the ways I see the commoner working itself out today.

I hope you'll check back in and join me.

Rebanks, James. The Shepherd's Life: Modern Dispatches from an Ancient Landscape. New York: Flatiron Books, 2015. p. 23. Rebanks regular uses the word "fell" or "fells" as a noun referring to what is known in Northern England as a "hill or stretch of high moorland" (Google search).

Perry, Michael. Truck: A Love Story. New York: Harper Perennial, 2006. p. 159.

Perry, Michael. Off Main Street: Barnstormers, Prophets & Gatemouth's Gator. New York: Harper Perennial, 2005. p. 72-73.

Fujimura, Makoto. Culture Care: Reconnecting with Beauty for our Common Life. New York: Fujimura Institute & International Arts Movement, 2015. Read the whole book, of course, but specifically the chapter titled "Culture Care Defined." [Kindle Version: location 1422-2146]

Rebanks. p. 218.

Berry, Wendell. "The Body and the Earth." In The Unsettling of America. Berkeley: Counterpoint, 2015 edition. p. 115-116.

Rebanks. p. 286.

Joy & Vision

Whatever is foreseen in joy

Must be lived out from day to day,

Vision held open in the dark

By our ten thousand days of work.

Harvest will fill the barn; for that

The hand must ache, the face must sweat.

- Wendell Berry

Here

"The birch is an abundant tree in my township and becoming more so, whereas pine is scarce and becoming scarcer; perhaps my bias is for the underdog. But, what would I do if my farm were further north, where pine is abundant and red birch is scarce? I confess I don't know. My farm is here."

- Aldo Leopold

"Driftwood: Time" [another old painting] & Understatement of Color

Much like the painting "Substance of Redemption" I wrote about on February 22, my painting "Driftwood: Time" was painted around the same time (exactly the year, again, I'm not sure). I had found a piece of driftwood near Lake Michigan and kept it around the house for quite a while. Like many artists, I had been working on numerous works at the same time. In my case, this particular work didn't start out as a painting of a piece of driftwood at all. Far from it. I was painting landscapes, trees, and the like. But I was looking to step out of my norm a bit and do something different involving multiple human figures in motion on this 8'x2' sheet of OSB or particle board (scrap material from a construction job site). It was planned to be a dramatic figurative study seeking to reflect both spontaneity (like the energy found in a sketch) and realistic figures.

I began planning to use only a blue hue to create a monochromatic piece. For whatever reason it didn't work. So before the oil paint dried I took a cloth and dampened it with linseed oil and some thinner and wiped down the surface. The effect turned out to be a glorious sky-blue "wash" that can be difficult to achieve with oils. I let it sit and dry. My hope was to preserve that wash and then use it as the underpainting for another image. However, what that image was to be I had no clue.

While working on other paintings, I noticed that piece of driftwood in my workspace. In real life it was only about a foot long and 4 inches wide in it's cylindrical form. It had this incredible hole to look through. I kept looking at it, did a couple charcoal drawings and decided that was the subject meant to be painted on that blue wash.

The result is what you can see in the accompanying image. Ironically, the imagery "feels" like those figures I had originally envisioned. I sought to keep a spontaneous feel full of contrast. What one might notice is the minimal "use" of that blue wash. I'm still struck by the fact that when I look at this painting I first think of that underpainting. Some might ask, "Why, then, if you loved that blue so much did you cover most of it up?"

The vibrant orange is certainly a compliment to the blue and so I began there; covering the entire background it seems to dominate. In fact, the orange does seem to take over. However, looking a bit longer you begin to focus on the hole in the driftwood and then the eye is drawn in two directions flowing along with the grain in the wood. In those grains are the slight dashes of blue, and if it isn't clear yet, that's my favorite part. The title, "Driftwood: Time," tells of my fascination with the amount of time it must take to shape a piece of wood into this gloriously smooth relic. The elements of wind, water, and sun patiently (albeit sometimes violently) sculpting something so intricate is a great mystery.

So through the seemingly infinite decisions made while producing work of art, I decided that that blue would be more powerful if it were understated. It's kind of like a scene of a movie or a section of a song that is so profound that you wish it would go on and on. At first I wish it would be longer, but then it occurs to me that the profundity would be dampened if the scene had lingered too long. The coming and going to that feeling is enhanced by it's understatement.

The painting was stored in Michigan with my friends Mike and Brooke Anderson for over a decade. They love art so much they put up with a heavy and awkwardly long piece of wood (driftwood?) while my family and I lived in Washington and for few years after we moved back to Michigan. They never complained, but Mike would remind me from time to time that it was there. Last fall I finally retrieved it and brought it home. It still hasn't found a good home or a place to be displayed.

The more I write about it, I'm struck by the fact that this painting tells my own story. I've learned enough to realize that we're always "waiting" for something, that life is constantly at play in the times of drifting. I feel most times like I'm drifting. However, true to the ever-popular Gandalfian wisdom, "Not all who wander are lost." It can feel like being lost at times, but there's motion and play and laughter and tears that are ever present. Perhaps it's true what I heard Andrew Wyeth say once in a documentary that we ultimately always paint ourselves. I suppose in one sense that is true: if we're true to out calling we will paint "ourselves," our unique vision for the world; much like a self-portrait. On the other side of that idea is the prospect of self-absorption. This is why we must share our work so that it doesn't just become a relic of "me." We share because we are nothing without others. The sharing is risky, of course, because some won't "get" it, or in the case of more abstract art some will get lost in trying to "figure it out." It's a risk worth taking, though, as we wander together in the various directions and delight in the things we discover.

My life and this painting have been cared for by numerous folks intent on enabling me to thrive in and through the drifting. The particle board has been minimally scuffed and bumped, it shows some wear but the life is still in it. I'm actually contemplating carefully cutting the painting into several smaller pieces. I'm not sure of the symbolism of this act, I think it would be intriguing to allow diverse people and homes to be able to encounter a piece of this old painting.

For a piece of driftwood, time is both a medium and a tool for clarity and beauty.

Substance of Redemption

I painted "Substance of Redemption" (see below) years ago, I would say sometime between 1998 and 2001, my father-in-law, Jim, and I were hired to do a unique project near Hamlin Lake (Ludington, MI). We were going to plant trees!

I don't recall what type of trees, and I don't know how the plot of land was cleared before hand. However, we planted saplings around which we wrapped translucent plastic tubes to aid in the gathering of sunlight and in order to protect the little trees from the deer.

Looking back now it may have been some of the most fascinating work I've had the privilege of doing (it tapped into what would eventually become my future agrarian interests as well). The site was secluded not far from a bridge Jim and I would later replace connecting two two-track "roads" for Hamlin's seasonal residents. [as an aside, that bridge project was where we were when the 911 attacks took place] However, our tree-planting work was meant to bring vitality back to a bare piece of land. To this day, and perhaps in part because of 911, that time, that work, and that place linger as a place of rejuvenating, concrete practice.

But the painting is also part of that story and that place. While we were working, I noticed another mature tree in the corner of the plot. A walnut, I think. It had the most unusually distorted form. It wasn't straight, but instead had what was a 90 degree jog from which it then went straight up into the canopy. The tree wasn't a runt, it seemed to be thriving, but it was not typical.

I decided to take my sketchbook to the site the next day and did some drawings during breaks in our work (Jim was always supportive of my artistic pursuits). What emerged was this painting. Further still, what I realized was what I think happened to that tree sometime in its history.

That walnut was wounded. It had been struck down or fallen upon by another tree. It may have been struck by lightening. Who knows for sure. It occurred me that the tree had overcome what, for some trees would have been a fatal blow, but it somehow grew back up and looked just fine other than the obvious "jog" in its form. Although abstract in color and feel, what is depicted in the painting is true to the form and dimension of the actual tree.

It is a symbol of redemption.

Soil

"This thing of soil conservation involves more than laying out a few terraces and diversion ditches and sowing to grass and legumes, it also involves the heart of the man managing the land. If he loves his soil he will save it."

- Henry Besuden; quoted by Wendell Berry in his essay "A Talent for Necessity"