He has to be on his knees…and chin himself.

Those are the words relayed to me from Andrew Wyeth through one of his biographers, Richard Meryman, back in 1998. As I was finishing college with a broad-based fine art degree, I began to intensely study the life and work of Mr. Wyeth. After graduating I read Meryman’s biography Andrew Wyeth: A Secret Life, which led to my writing to the artist himself, the story of which I’ll come back to a bit later…

…In the meantime, I will admit that my interest in Wyeth bordered on an obsession. It started at some point with viewing perhaps his most famous painting, “Christina’s World,” in several books (to this day I’ve yet to see the painting in person) and for all it’s “realism” (for which Wyeth was both praised and criticized by his contemporaries) is as “surreal” a work of art as anything labeled such. In fact, I would contend that it may be more surreal. Because, you see, for all the narrative back-story, the masterful egg tempera techniques, and the lovely yet altogether discomforting pose of the figure, there’s still something “off” about the composition, the work succeeds by transporting the viewer further into the subconscious. I should add, however, that I don’t mean to force his work into that category, but it is how I’ve interacted with it. Perhaps a better way of framing it is as a “concrete surrealism” that draws out the glory of everyday things. Which is why the criticisms leveled against his work as “sentimental” or “photorealist” annoy me. You really must let it interpret you.

Spend any amount of time meditating on Wyeth’s iconic works, and you begin to see this visual-off-ness that pushes the work beyond strict realism for realism’s sake. From his “Winter 1946” to “Marriage" to the haunting “Adrift” or “Pentecost” there’s always a piece of the perspective and the modeling that defies the notion of a pretty picture. And therein lies Andrew Wyeth’s brilliance: he created works that are never flawless but they are perfect. He took that thing that looks real (which it is) and yet invites us to see both that thing or person and something more.

Even if I had never known about the story of Christina Olsen from the books about the painting, “Christina’s World” captivates because as you allow it to simply be and interpret you (the viewer) the not-flawless-yet-perfect visual story unnerves and delights. The contorted figure struggles toward a home, one that may or not feel like a home. The house itself sits awkwardly right on top of the horizon line. The two-track partially hinted at is no where near the lonely figure, which further alienates the subject. The faded pink of Christina’s dress contrasts (flawlessly in this particular case) with the overwhelming earth-tones of the rest of the composition which hints at the presence of life in a place that may be struggling to stay alive. There is more, of course, but the depth of this work would never have been accomplished had the artist sought to paint the scene exactly as it looks in real life.

At this point I ought to get back to the topic of this essay. However, a few words about who Richard Meryman was. The highlights are that he was a longtime journalist for Life magazine whose well known for having published an interview with Marilyn Monroe just two days before she passed away. He interviewed a wide-array of entertainers and celebrities. Should you do a search of his name online, you will find plenty of information about his life and work. From my understanding, he and Andrew Wyeth were considerably close which was apparent to me, at least, as I read his book. To be certain, one’s life isn’t simply a list of bullet points, and I expect there’s so much more that includes joy and sorrow that is Richard Meryman. My tale here certainly demonstrates a legacy of kindness and generosity even to a stranger using him as a “mediator” to someone else.

I wrote this letter to Andrew Wyeth in 1998. Handwritten, no copies, so no archive of it other than (perhaps but most likely not…and that’s okay) in some box buried at the Wyeth estate. All I have are the short notes sent to me from Richard Meryman that will have to suffice. I’m pretty sure I thanked Wyeth for his work and impact on my own life and work. I was particularly fascinated by the lifelong discipline it took to become a master of his craft, a discipline that I can only imagine even in my own practice. For it is clear he was just that, a master. I also celebrated his commitment to “realism” in the face of other abstract expressionist work that had grown in popularity during his lifetime. All those things I’m sure I addressed in my letter.

To be honest, though, I doubted I would ever hear anything back. So it was a surprise to receive the following letter from Mr. Meryman (I had written to him through the HarperCollins address) within a couple weeks! It read:

Dear Edward Traub -

As you see, I have received your letter and your wonderful, (moving) sentiments. I am going down to see Wyeth next week and will deliver your letter by hand. I know he will be very touched and pleased -

Richard Meryman

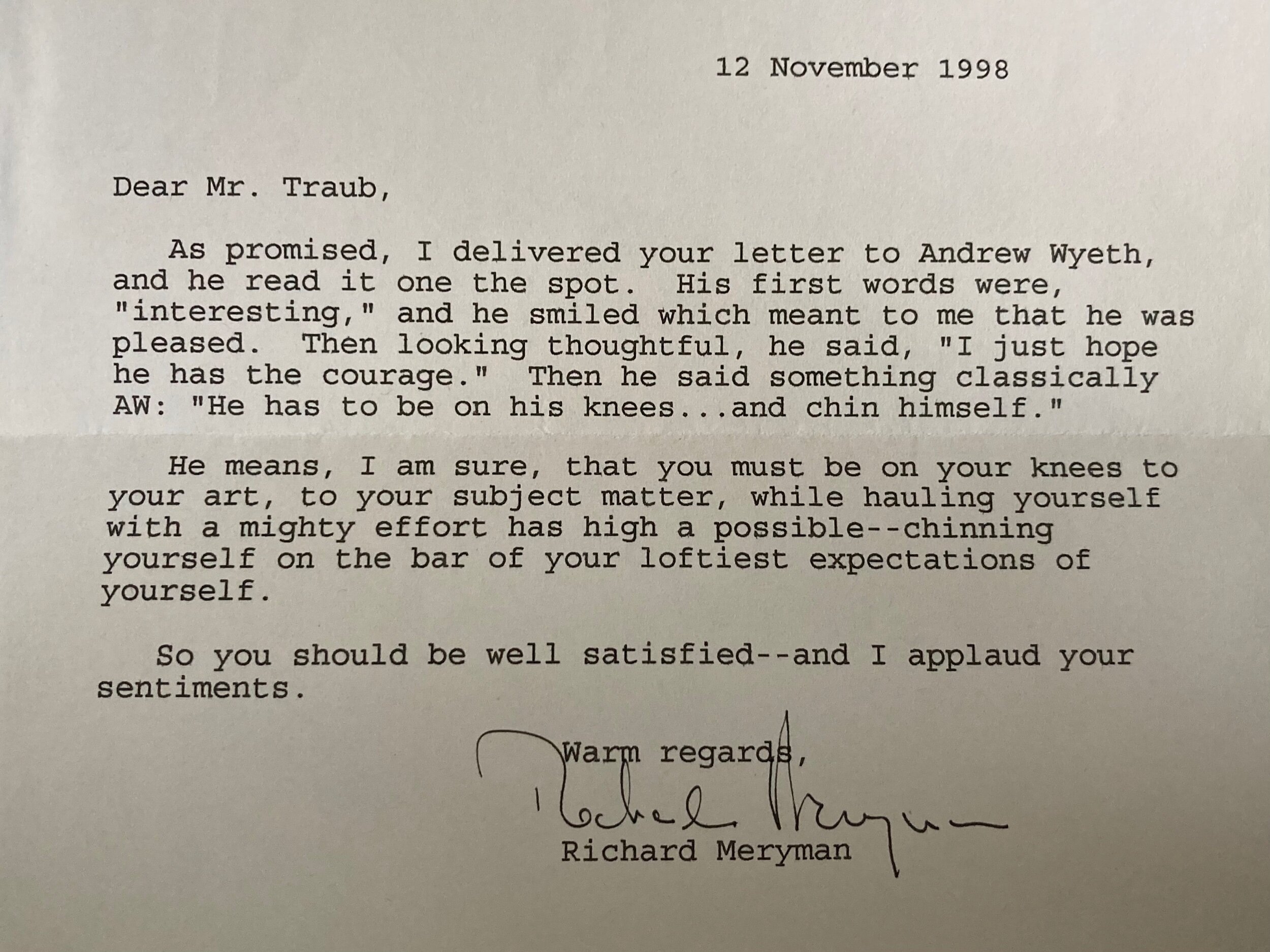

I was ecstatic, of course, and content with that. I had no expectation of further correspondence. But again, I was mistaken. In a few short days I received another note from Mr. Meryman dated “12 November 1998”:

Dear Mr. Traub,

As promised, I delivered your letter to Andrew Wyeth, and he read it on the spot. His first words were, “interesting,” and he smiled which mean to me that he was pleased. Then looking thoughtful, he said, “I just hope he has the courage.” Then he said something classically AW: “He has to be on his knees…and chin himself.”

He means, I am sure, that you must be on your knees to your art, to your subject matter, while hauling yourself with a mighty effort (as) high (as) possible — chinning yourself on the bar of your loftiest expectations of yourself.

So you should be well satisfied — and I applaud your sentiments.

Warm regards,

Richard Meryman

Years later I still read these letters with delight and with a sense of calling. My wife and I have discussed these words a number of times, and I have yet to find a clearer way to describe my approach to life and work. As an artist, it is with some trepidation that I confess my waywardness in such a commitment to my art. I am a polymath, easily moved from one discipline to the next (something I try to embrace as a strength…which it can be) and my painting style has been at times lacking in focus. Those who know me and my paintings will probably be surprised to associate Wyeth with having impacted my work. However, another friend did describe my work as a cross between Andrew Wyeth and Mark Rothko; a humbling yet somewhat accurate description.

For years I sought to work, and taught others to work, at least as a starting point, from some level of “realism,” which I consider a deep attentiveness to what “is” and then from there an artist can branch out. Until one participates in this deep practice in careful observation, they can never authentically move abstractly. I credit my friend and distant mentor, Makoto Fujimura, for guiding me in my coming to grips with realism and abstraction and so I journey on in waves of productivity and dryness.

He has to be on his knees…and chin himself.

I’m grateful for these words. I’m still amazed that Andrew Wyeth read my letter. Sometimes I wonder what it would be like to have met him in person; and yet this tale suffices perhaps more powerfully to demonstrate that even the simplest interaction can shape someone’s life for going on twenty years now.

As profound as the words Wyeth spoke are, this essay is also a tribute to Mr. Meryman. He didn’t have to do what he did, and yet he considered it important enough to deliver my letter in person. He encouraged this artist by allowing me an opportunity to encourage another (albeit a “famous” artist). Wyeth’s words echo daily in my work, no matter what or where, as I explore things that are important to me, to kneel down in order to understand my subject, be it cultural and societal issues ranging from racism to farming, to my own art practice and life with my family. There will always be that tension between submission and effort. The work (“chinning”) is the part that can be the most vulnerable. These things are what Andrew Wyeth called out in me.

Postscript: through the (sometimes) wonderful world of social media I have recently reached out to Mr. Wyeth’s only grandchild, Victoria Browning Wyeth, who encouraged me to write this. She is passionate about her family’s work and sharing it with the world. Many thanks to her.

[Thanks for reading. Please feel free to join me here, but also promise to read and engage thoughtfully and with a generative spirit keen on cultivating a better world along the way.]