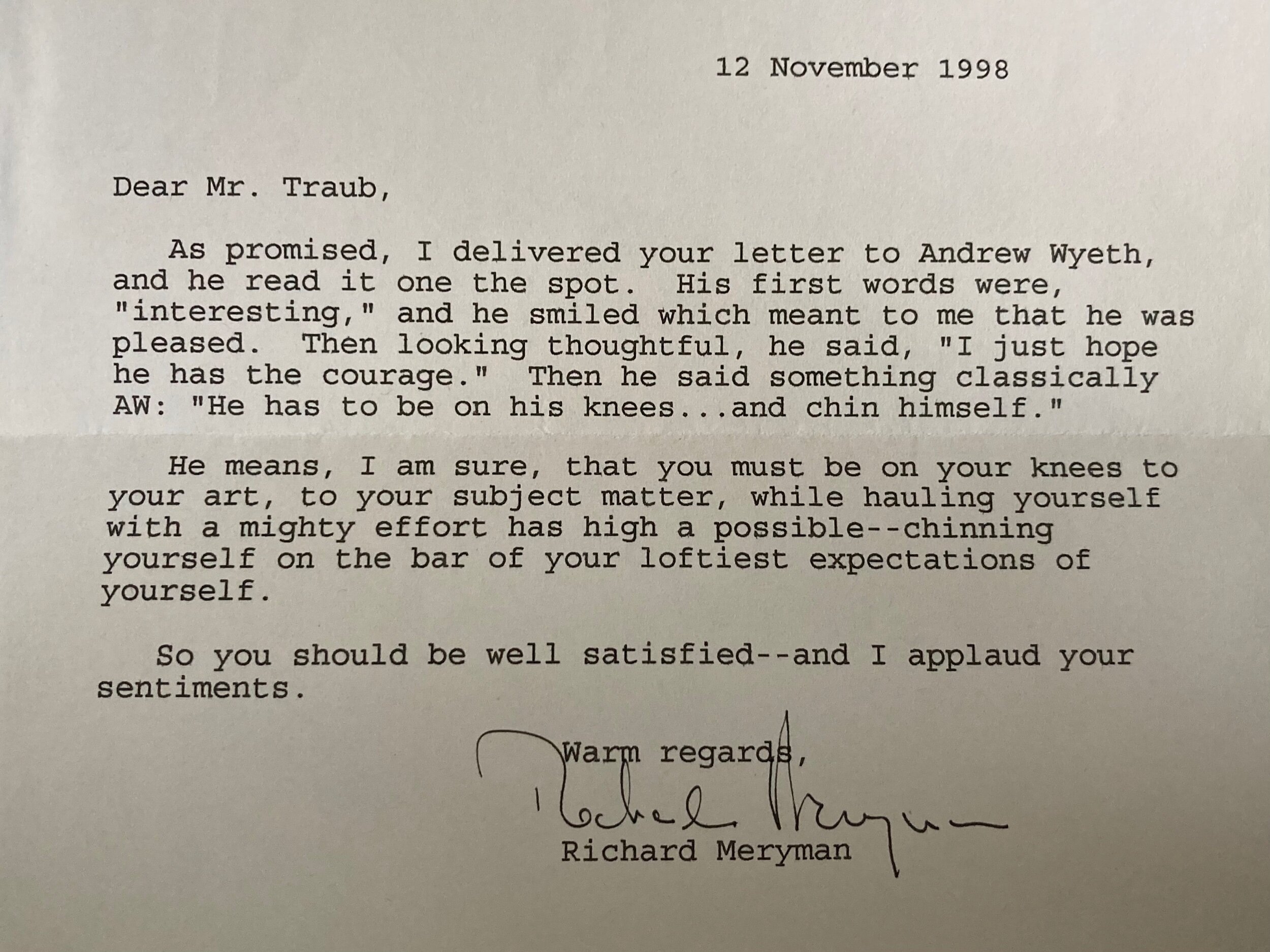

Much like the painting "Substance of Redemption" I wrote about on February 22, my painting "Driftwood: Time" was painted around the same time (exactly the year, again, I'm not sure). I had found a piece of driftwood near Lake Michigan and kept it around the house for quite a while. Like many artists, I had been working on numerous works at the same time. In my case, this particular work didn't start out as a painting of a piece of driftwood at all. Far from it. I was painting landscapes, trees, and the like. But I was looking to step out of my norm a bit and do something different involving multiple human figures in motion on this 8'x2' sheet of OSB or particle board (scrap material from a construction job site). It was planned to be a dramatic figurative study seeking to reflect both spontaneity (like the energy found in a sketch) and realistic figures.

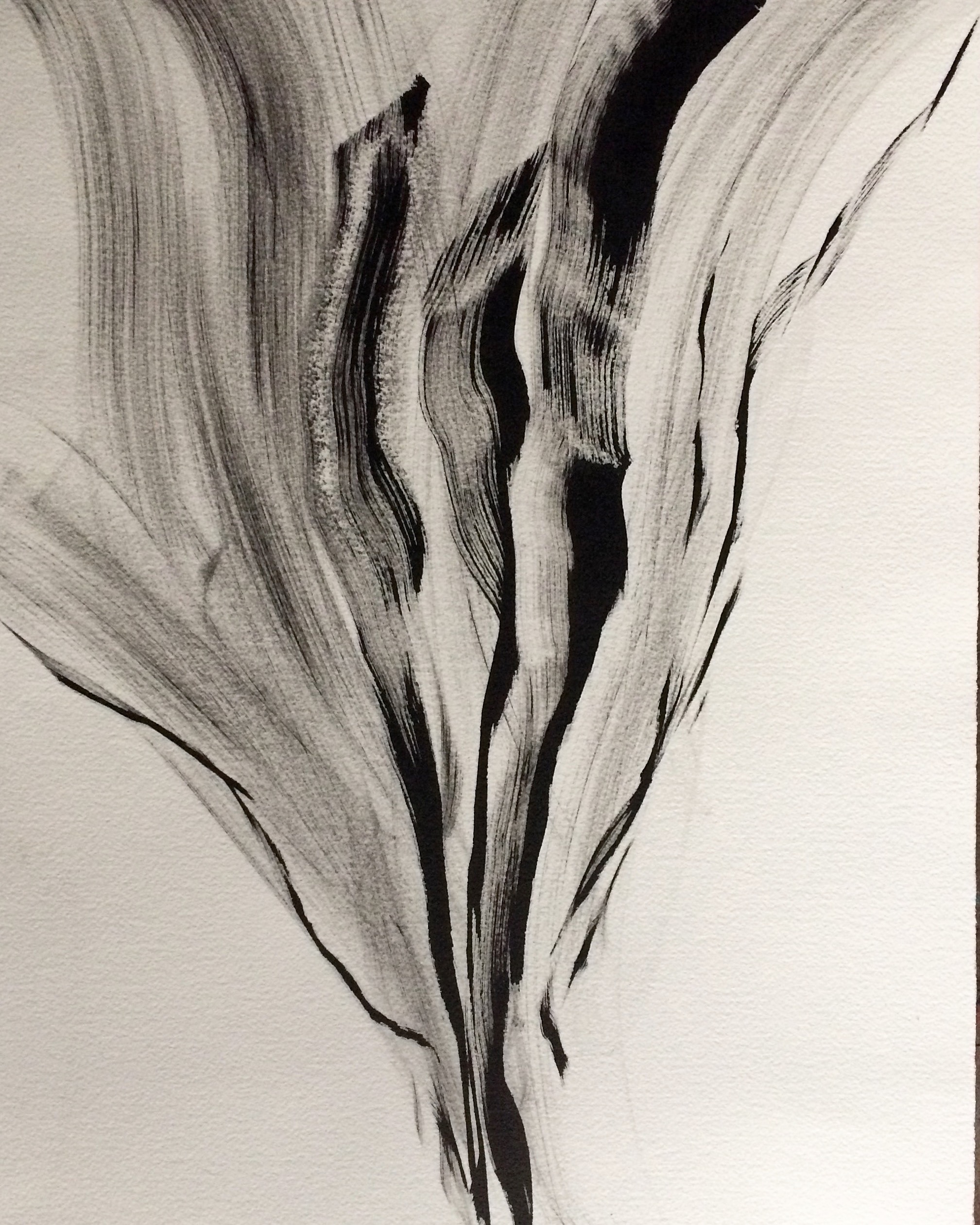

I began planning to use only a blue hue to create a monochromatic piece. For whatever reason it didn't work. So before the oil paint dried I took a cloth and dampened it with linseed oil and some thinner and wiped down the surface. The effect turned out to be a glorious sky-blue "wash" that can be difficult to achieve with oils. I let it sit and dry. My hope was to preserve that wash and then use it as the underpainting for another image. However, what that image was to be I had no clue.

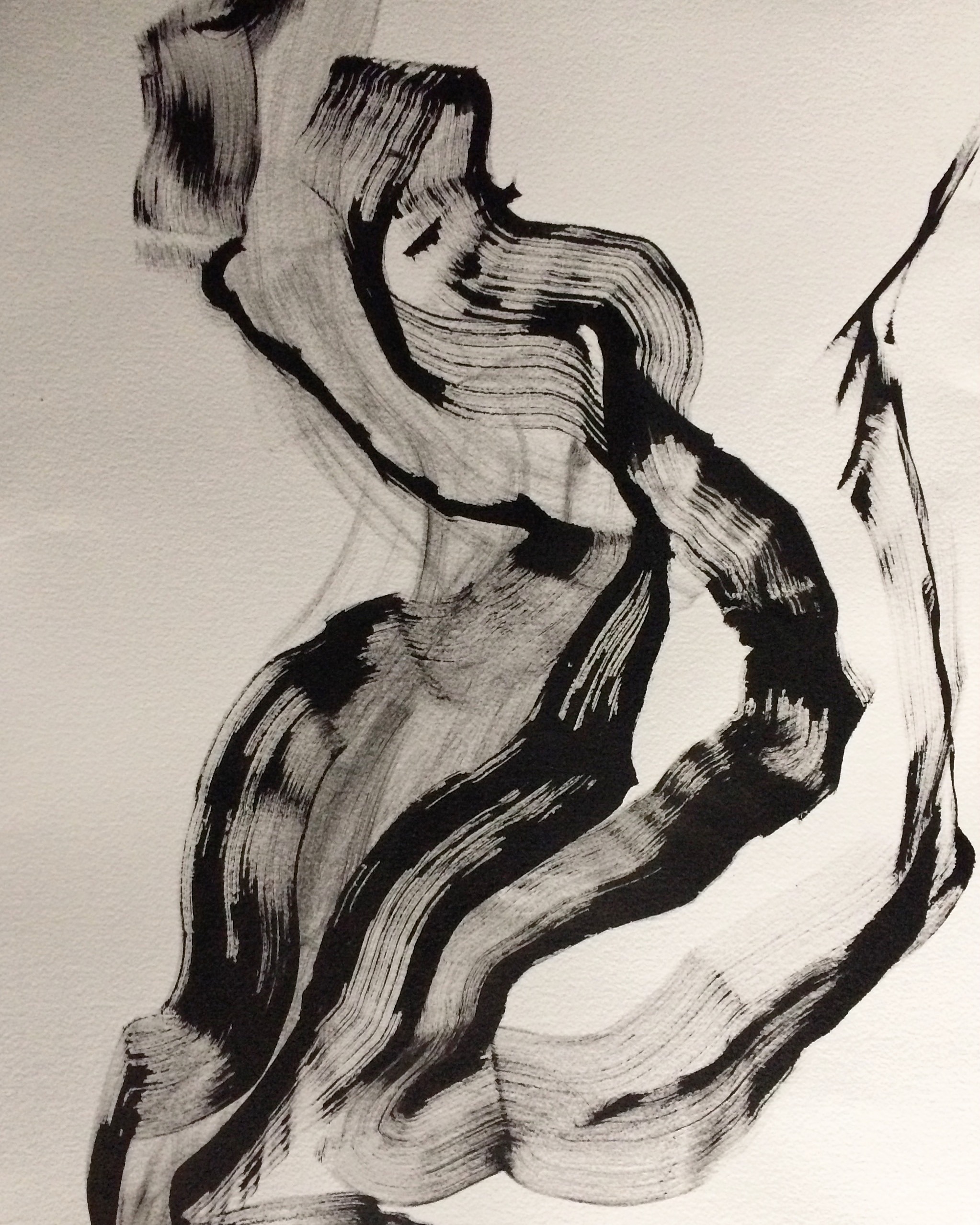

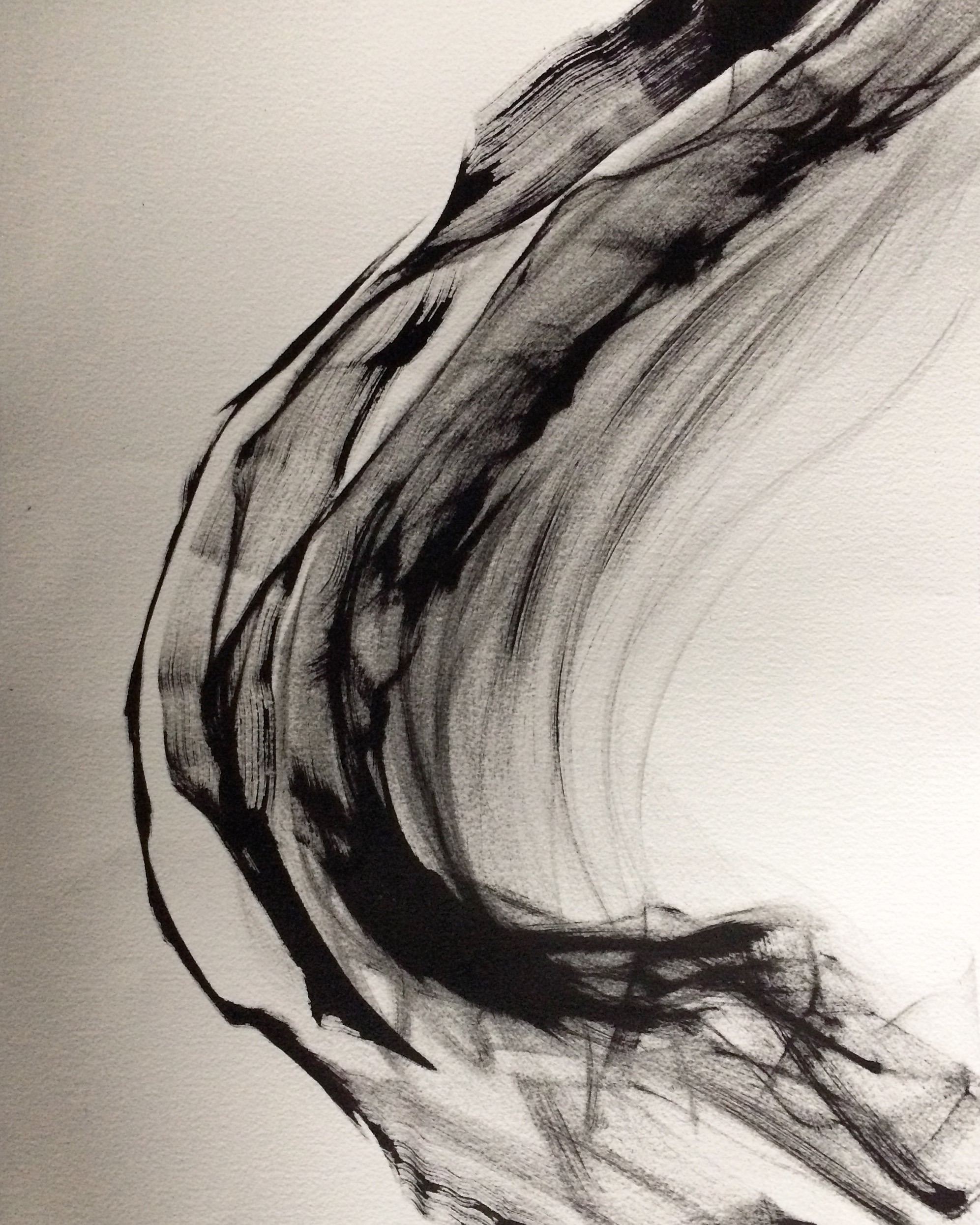

While working on other paintings, I noticed that piece of driftwood in my workspace. In real life it was only about a foot long and 4 inches wide in it's cylindrical form. It had this incredible hole to look through. I kept looking at it, did a couple charcoal drawings and decided that was the subject meant to be painted on that blue wash.

The result is what you can see in the accompanying image. Ironically, the imagery "feels" like those figures I had originally envisioned. I sought to keep a spontaneous feel full of contrast. What one might notice is the minimal "use" of that blue wash. I'm still struck by the fact that when I look at this painting I first think of that underpainting. Some might ask, "Why, then, if you loved that blue so much did you cover most of it up?"

The vibrant orange is certainly a compliment to the blue and so I began there; covering the entire background it seems to dominate. In fact, the orange does seem to take over. However, looking a bit longer you begin to focus on the hole in the driftwood and then the eye is drawn in two directions flowing along with the grain in the wood. In those grains are the slight dashes of blue, and if it isn't clear yet, that's my favorite part. The title, "Driftwood: Time," tells of my fascination with the amount of time it must take to shape a piece of wood into this gloriously smooth relic. The elements of wind, water, and sun patiently (albeit sometimes violently) sculpting something so intricate is a great mystery.

So through the seemingly infinite decisions made while producing work of art, I decided that that blue would be more powerful if it were understated. It's kind of like a scene of a movie or a section of a song that is so profound that you wish it would go on and on. At first I wish it would be longer, but then it occurs to me that the profundity would be dampened if the scene had lingered too long. The coming and going to that feeling is enhanced by it's understatement.

The painting was stored in Michigan with my friends Mike and Brooke Anderson for over a decade. They love art so much they put up with a heavy and awkwardly long piece of wood (driftwood?) while my family and I lived in Washington and for few years after we moved back to Michigan. They never complained, but Mike would remind me from time to time that it was there. Last fall I finally retrieved it and brought it home. It still hasn't found a good home or a place to be displayed.

The more I write about it, I'm struck by the fact that this painting tells my own story. I've learned enough to realize that we're always "waiting" for something, that life is constantly at play in the times of drifting. I feel most times like I'm drifting. However, true to the ever-popular Gandalfian wisdom, "Not all who wander are lost." It can feel like being lost at times, but there's motion and play and laughter and tears that are ever present. Perhaps it's true what I heard Andrew Wyeth say once in a documentary that we ultimately always paint ourselves. I suppose in one sense that is true: if we're true to out calling we will paint "ourselves," our unique vision for the world; much like a self-portrait. On the other side of that idea is the prospect of self-absorption. This is why we must share our work so that it doesn't just become a relic of "me." We share because we are nothing without others. The sharing is risky, of course, because some won't "get" it, or in the case of more abstract art some will get lost in trying to "figure it out." It's a risk worth taking, though, as we wander together in the various directions and delight in the things we discover.

My life and this painting have been cared for by numerous folks intent on enabling me to thrive in and through the drifting. The particle board has been minimally scuffed and bumped, it shows some wear but the life is still in it. I'm actually contemplating carefully cutting the painting into several smaller pieces. I'm not sure of the symbolism of this act, I think it would be intriguing to allow diverse people and homes to be able to encounter a piece of this old painting.

For a piece of driftwood, time is both a medium and a tool for clarity and beauty.